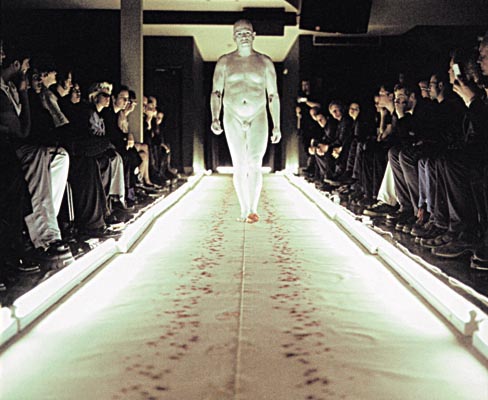

People gather on both sides, the lights are still off. The photographers at the end of the catwalk, cameras in hand wait for the gold shot. The atmosphere is tense; this is definitely not London Fashion Week.

Suddenly the lights are switched on revealing the catwalk made of canvas - the show is about to start. A fat naked man appears at the top and starts walking down towards the cameras; his body is covered in white paint and there is silence. The fat white man bleeds from both arms the blood that paints the canvas red. The gold shot.

The air is fresh, fast and confident like in any other September morning. The yellow cabs, the rush, the success, the smell of coffee, money and hope, that weird feeling of "today I'm gonna make it. Today I won't fail." It's morning in downtown Manhattan and in a couple of minutes and three blocks down two sister towers will give birth to a monstrous hole covered in blood and anger, (another) bastard child of Humanity.

These two events - one taking place in the space of an art gallery turned institution of global art and the other in a financial district turned institution of global trade - have at least two things in common: both offer themselves for aesthetic judgement and both have a strong political intent in the sense that both can potentially change the order of things.

When writing about the aesthetic judgement, Kant pointed out its division in two categories, the Beautiful and the Sublime. If the pleasure of the beautiful comes with the apprehension of an object that is in harmony with the ideas of our understanding, i.e. with the world-as-we-know-it, the pain of the sublime happens when our understanding is presented with an object that is so big and/or so powerful that (1) it refuses to be thrown into one of the boxes in which we usually try to fit the world and (2, and by consequence) it immediately and painfully questions our knowledge of it.

It is easy to grasp the political character of the sublime. The sublime is the violent and painful feeling that is generated in us when we experience something "too big for words." Something that challenges the way we order the real. Something that might ignite change. The unspeakable.

Let's know think violence. Let's say in a simple way that violence happens when a force A meets another force B and ends up changing the properties (intensity, direction) of the latter, changes that B would never suffer wouldn't it be for A. (An object always offers resistance to any change in its condition - this is what physics called 'inertia' and philosophy, via Spinoza, called 'connatus').

In consequence, we arrive to the point where violence equals politics (equals violence). If violence is the action of A that will cause - or contribute for - a change in B, violence is politics. And it is my view that politics cannot be made without a certain degree of violence. Violence is always already at the very core of becoming (something else).

My question, or better, the problem I would like to throw at you as it were, is an ethical one. To which extent shall one embrace violence in order to bring change? To which extent shall art embrace violence? When is it better to stop (and maybe rethink the strategy)? Is there an absolute limit or is it all about negotiating the limits along the way? Will the aim ever justify the means? What can one do? And how? On an ethical level, what makes the difference between the work of, let's say, Franko B and that of a terrorist group that hits towers with airplanes? WHere does art end and terrorism start? Could (some) terrorist acts ever become art?

Franko B once said:

My work focuses on the visceral, where the body is a site for representation of the sacred, the beautiful, the untouchable, the unspeakable, and for the pain, the loss, the shame, the power and fears of the human condition... Detractors will say that I make monstrous work, and in a way it is: the Latin root monstrare means to show. If a monster is therefore something that shows itself as much as it is seen by you, then let me be a monster.*

(*from Franko B, "I Miss You!" in, Adrian Heathfield (ed.), Live: Art and Performance, 2004, London: Tate Publishing)

1 comment:

Any form of human progress involves a conflict. However, nihilism as expressed by the terrorists of 9/11 is pure destruction and a hatred of human life (similar in outlook to eco-fascists and environmentalists). Franko's performance expresses a love of life - there is no death - it's a meditation on, and celebration of the very form that we inhabit - the human body and it's life force - blood.

Post a Comment